Co-creating Future Strategies from the Grassroots Stories: Covid-19 and Internal Migration in Eastern Assam

Noesis Literary Volume 2 Issue 2 (July-Dec) 2025, pp: 113-130

Dr. Alankar Kaushik

Assistant Professor

EFL University, Shillong Campus

Department of Journalism and Mass Communication

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-4021-7777

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.69627/NOL2024VOL2ISS2-08

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed deep fissures in India’s socio-economic landscape, exposing the precarity of internal migrant workers. Assam, particularly its eastern districts, became a compelling site of observation when tens of thousands of labourers were compelled to return home after the national lockdown in March 2020. This paper critically engages with those migratory experiences through The Migration Tale Animation Project, a participatory storytelling intervention co-created with Brahmaputra Foundation for Social Research and Livelihood Practices,Dibrugarh commissioned by IATSS Forum, Japan. The project transformed oral testimonies of select migrant labourers from tea garden, riverine, and tribal communities into animated stories that circulated through digital platforms and village screenings. Drawing on Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model, Arjun Appadurai’s notion of mediascapes, and Everett Rogers’s diffusion of innovations, this paper argues that participatory animation operates as a dialogical form of communication for social change. By situating animation as a vernacular pedagogy of resilience, the study not only documents the socio-cultural aftermath of migration but also demonstrates how aesthetic participation can reclaim narrative sovereignty, foster empathy, and co-produce future strategies for community resilience in post-pandemic Assam.

Keywords: internal migration, Assam, participatory animation, storytelling, communication for social change, community media.

Introduction

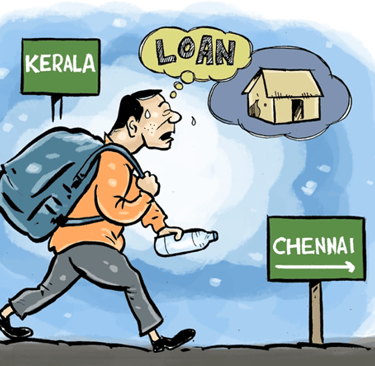

Migration, both internal and external, has long shaped India’s social and cultural cartography. Yet, the Northeast region remains an underrepresented geography in migration discourse, often overshadowed by narratives of in-migration and ethnic conflict rather than out-migration and labour precarity. Within Assam, the phenomenon of migration is entangled with histories of economic marginalization, linguistic politics, and environmental vulnerability. However, when the COVID-19 lockdown was announced on March 25, 2020, it abruptly disrupted the circular migration of Assamese labourers across India’s industrial belts. Workers employed in manufacturing, construction, and service sectors in Kerala, Chennai, and Haryana suddenly found themselves stranded without income or social protection. The return of nearly 1,73,000 migrants to Assam not only tested the capacity of the state but also challenged the dominant narratives of belonging and labour mobility (PTI 2020)

Mainstream media’s representation of these events was strikingly limited, mostly episodic, lacking context, and devoid of empathy. Migrants were framed as either helpless returnees or potential virus carriers rather than as skilled laborers and social actors embedded within complex translocal circuits of livelihood. Against this backdrop, The Migration Tale Animation Project sought to reclaim the migrant’s voice through participatory storytelling, using animation as a medium of communication and reflection. Conceived as a collaboration between Brahmaputra Foundation for Social Research and Livelihood Practices (BRFRLP) across Dibrugarh, Dhemaji, and Sivasagar districts, the project translated real-life narratives of select return migrants into short animated films in Assamese and Sadri, accompanied by local music and community narration.

The project’s central premise was that storytelling, when co-created with participants, can transform data into dialogue, emotion into awareness, and representation into empowerment. Animation often dismissed as entertainment was here mobilized as a participatory pedagogical tool capable of simplifying complex policy issues while preserving emotional depth and local aesthetics. As Freire argues, dialogical communication transforms the act of telling into an act of knowing, enabling participants to become both narrators and subjects of their own history (Freire 68).

Literature Review

Migration studies in India have evolved from demographic and economic analyses to more nuanced social and cultural readings. Yet, the Northeast continues to occupy a peripheral space in this literature. According to the 2011 Census, over one million individuals from the region were living outside their home states, representing approximately 2.2 percent of its population (Singh 245). Migration from Assam, particularly from its eastern districts, has historically been linked to agrarian stagnation, limited industrial opportunities, and the precarities of the informal labour market. Recent studies indicate an increasing shift of migrants from North and East India toward the southern industrial corridors of Chennai, Kerala, and Bangalore due to better wages and safer work environments (Arya 74; Narayana and Venkiteswaran 2013; Deori 2016; Kiruthiga and Magesh 97; Marchang 43).

While economic analyses dominate the field, the role of media in shaping migrant identity and public imagination remains understudied. Elkins and Morton argue that the media not only represent migration but also mediate it, influencing both aspirations and anxieties associated with mobility. Images circulated from destination sites create imagined geographies of opportunity that may or may not align with migrants’ lived realities. Conversely, home-region media often frame migrants as absent subjects reduced to remittances or returnees rarely acknowledging their experiences as dynamic actors in the circuits of production and social change.

The emergence of participatory and community media initiatives such as Brahmaputra Foundation (BFSRLP) challenges this representational deficit by emphasizing horizontal communication. Freire’s dialogical model situates media as a process of conscientization a means of fostering critical consciousness through collective reflection and action. Similarly, Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding theory reminds us that media meaning is not unidirectional; audiences actively interpret, negotiate, or resist dominant codes (Hall 136). In the context of Assam’s migration narratives, participatory animation thus becomes a site of negotiation where migrants reinterpret their experiences and rearticulate belonging through visual language.

From a theoretical standpoint, Thomas Nail’s Figure of the Migrant introduces the concept of kinopolitics, the politics of movement as central to understanding migration. Rather than viewing migrants as passive victims, Nail positions them as agents of circulation and transformation (Nail 15). This resonates with the Assamese experience, where mobility is not merely economic but deeply political, intertwined with histories of displacement, riverine erosion, and ethno-linguistic exclusion. By combining these perspectives, Freire’s dialogical pedagogy, Hall’s cultural negotiation, and Nail’s kinopolitics, this study situates participatory animation as a cultural practice that visualizes movement, displacement, and hope.

Methodology

This study adopted a mixed-methods and participatory research design across three districts of Eastern Assam namely Dibrugarh, Dhemaji, and Sivasagar. Fieldwork covered nine villages representing tea garden, riverine, and non-tribal mainland communities. Data collection combined surveys, ethnographic interviews, and participatory cultural production. The goal was not only to document migrant experiences but to co-create communicative spaces for self-expression and dialogue.

Quantitative and Qualitative Stages:

Socioeconomic Mapping: Household-level surveys captured migration histories, income patterns, and pandemic-related livelihood disruptions. Out of 1,841 households, 9.39 percent of youth were identified as migrants employed either within or outside Assam in manufacturing, service, or construction sectors.

In-depth Interviews: Semi-structured interviews recorded individual experiences of migration, financial adaptation, and reintegration during the lockdown. Respondents were selected to represent gender, age, and community diversity.

Participatory Animation Workshops:

The most significant methodological innovation was the introduction of the storytelling practices for intiating dialogue among the select participants. Participants worked with facilitators from Brahmaputr Foundation to script, narrate, and visualize their own migration tales. Each story was adapted into a 5–7 minute animated short using open-source software (OpenToonz and Synfig Studio). The participants under the supervision of a recognised animator from Assam contributed illustrations, and participants voiced their characters in Assamese and Sadri language. The completed animations were screened in community halls generating feedback and discussions among viewers.

This participatory model aligns with John Dewey’s experiential learning philosophy, which emphasizes learning through doing, and Everett Rogers’s diffusion of innovations theory, which views communication technologies (like animation) as tools for spreading new ideas through social networks. Here, animation functioned as a social innovation, a new medium for knowledge exchange, empathy-building, and collective reflection.

Ethical considerations remained central throughout the process. Participants retained ownership of their stories, consented to the adaptation of their narratives, and received digital copies of their animations. All visual content avoided stereotyping, ensuring dignity and agency in portrayal.

Migration Tale: Storytelling and Animation as Participatory Communication

The Migration Tale Animation Project emerged as both method and medium, an experiment in transforming qualitative data into participatory media for social change. The process drew on Paulo Freire’s conviction that dialogue is the essence of liberation. Instead of being “objects” of research, migrants became co-authors of their stories. The act of visualizing one’s narrative seeing it animated on screen functioned as what Freire calls an act of naming the world, a reclaiming of one’s social being through language and representation (Freire 76).

The Migration Tale approach also resonates with Arjun Appadurai’s concept of mediascapes, which situates media as global terrains of image and imagination. In this project, animation became a vernacular mediascape, a space where local aesthetics met digital storytelling to circulate experiences of migration in culturally legible forms. The use of Assamese idioms, folk motifs, and regional music grounded the animation in local sensibilities while connecting to global circuits of visual activism.

At the theoretical intersection of Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding and Everett Rogers’s innovation diffusion, participatory animation operates as a communication loop. Migrants encode their experiences through animation (production), audiences decode them through screenings and discussions (reception), and feedback re-informs both narrative and policy understanding (diffusion). The iterative process thus becomes dialogical, reciprocal, and transformative.

In practice, the Migration Tale series visualized five narratives those of Bijoy, Biswajit, Rubi, Shyam, and Durlov. Each animated story corresponded to a distinct migration trajectory, yet collectively they revealed structural continuities of exclusion, aspiration, and resilience. The screenings attracted over 1,200 villagers across nine locations, followed by interactive discussions on labour rights, financial planning, and health awareness. Radio broadcasts later expanded the audience base, ensuring that migrant families, including those still working outside Assam, could listen to the stories in serialized audio form.

Through animation, abstract policy failures became tangible, and individual emotions became public pedagogy. The participatory process encouraged critical dialogue among viewers, aligning with Freire’s problem-posing education learning through the recognition of contradictions and the search for collective solutions.

Transition to Findings: The following section situates the five animation-based migration tales within this participatory framework, analyzing how each narrative exemplifies communication for social change through storytelling, empathy, and local visual culture.

Findings and Analysis : The five animated stories Bijoy, Biswajit, Rubi, Shyam, and Durlov constitute the ethnographic heart of The Migration Tale Animation Project. Each animation translated lived experience into participatory media, where drawing, voice, and rhythm functioned as communicative acts of self-representation. The process affirmed that animation, far from being a merely aesthetic exercise, can visualize structural inequalities and offer platforms for social pedagogy.

Bijoy Kheruwar: Debt, Return, and Economic Reintegration: The animation “Bijoy’s Return” opens with the image of a bamboo bridge over the Burhidihing River, symbolizing both separation and reconnection. Bijoy’s narrative portrays a young tea-garden worker who migrated to Kerala at fifteen to repay a family mortgage. His animated self, drawn in earthy browns and greens, is shown sanding furniture while a voice-over in Sadri recounts his first remittance home. The story ends with his mother unlocking the wooden chest that once held their debt papers.

From a communication-for-development perspective, Bijoy’s story demonstrates Rogers’s diffusion of innovations: the remittance habit, savings culture, and debt-free narrative diffused through community screenings, prompting local discussions on financial literacy. Animation enabled abstract economic behaviour like saving, investment, entrepreneurship—to be rendered emotionally legible. During post-screening dialogues, villagers collectively articulated micro-plans for home-based businesses, reflecting Dewey’s experiential learning cycle in practice.

Biswajit Saikia: Skill, Loss, and Translocal Identity

In “Biswajit’s Workshop,” the screen fills with rotating plywood sheets, each cut revealing a memory of displacement. Biswajit’s life from Dimapur caretaker to Haryana carpenter was visualized as a montage of wooden textures. The animation employed rhythmic hammer sounds drawn from Assamese Bihu beats, linking labour with culture.

Hall’s encoding/decoding model is crucial here. Biswajit encoded his identity as an artisan rather than as an exploited worker. Audiences in Moran decoded this meaning not merely as pride but as critique, a call for state-supported vocational training. His narration in Assamese also reflected Appadurai’s mediascapes, where linguistic hybridity mirrors migratory fluidity. Community youth later reported that the film challenged the stigma associated with manual labour, validating skill as dignity.

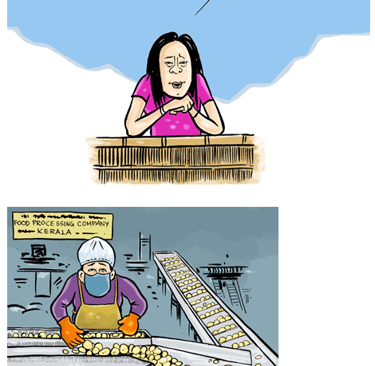

Rubi Moran: Gendered Migration and Emotional Labour

Rubi’s animation, “She Lives It,” reimagined her domestic trauma and migration to Kerala through a surreal colour palette of blues and yellows. Scenes of seafood packaging factories were intercut with childhood memories in Betoni Gaon, producing a counter-archive of feminine resilience.

Drawing on Freire’s participatory pedagogy, the team structured Rubi’s storytelling workshop as a circle of dialogue with other women returnees. Discussion centered on financial autonomy and safety. The animation became a collective text through which women negotiated identity beyond victimhood. The animation also visualized affective labour, the unseen emotional and care work sustaining families of migrants. Through Rubi’s calm narration, the narration destabilized patriarchal tropes, showing that empowerment resides not only in leaving but also in sustaining.

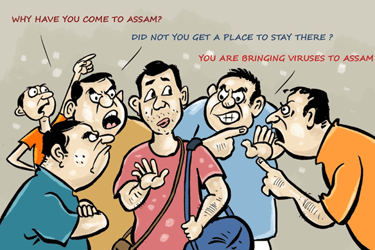

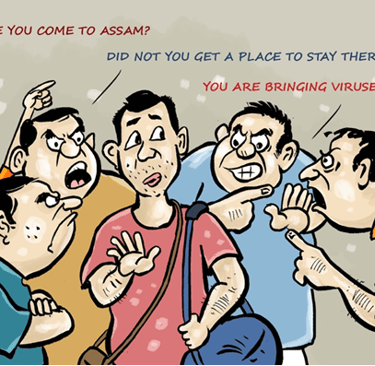

Shyam Baruah: Stigma, Mobility, and the Politics of Recognition

Shyam’s story, “You Are Bringing Viruses to Assam,” dramatized the double marginalization migrants face racialized outside the state, stigmatized within. The animation employed split-screen technique: one side showing Chennai’s neon streets, the other, Assam’s rural quarantine center. Sound design layered Tamil street noise over Assamese folk drone, producing cognitive dissonance that mirrored Shyam’s alienation.

The sequence exemplifies Nail’s kinopolitics, visualizing how movement itself becomes politicized. Shyam’s body is rendered as a figure in perpetual motion, neither settled nor belonging echoing Nail’s idea of the migrant as the “constitutive outside” of political community (Nail 32). Post-screening conversations in Tinsukia generated reflections on social stigma and empathy. Viewers identified with Shyam’s humiliation and linked it to local exclusion practices toward inter-district workers, demonstrating the animation’s power to trigger critical consciousness in Freirean terms.

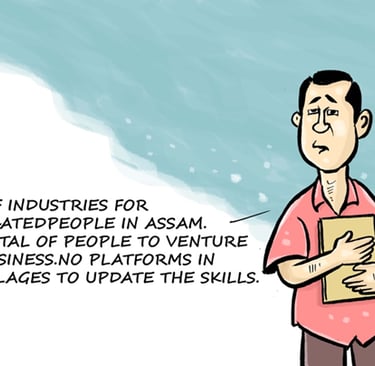

Durlov Rajbangshi: Displacement, Skill, and Hope

“Optionless and Unhappy” follows Durlov’s departure from Binoigutia after family debt and betrayal by a contractor. The animation alternates between grayscale sketches of unemployment and bursts of colour during scenes of his factory work in Chennai, symbolizing ambivalence between exploitation and aspiration.

The narrative illustrates Appadurai’s cultural reproduction, where imagination becomes a social resource. Despite alien conditions, Durlov dreams of returning to start a farm using “scientific methods.” The animation concludes with a shot of sprouting paddy rendered in time-lapse watercolour followed by a freeze-frame on Durlov’s smile. In screenings, villagers interpreted this as both literal and metaphorical cultivation, inspiring youth discussions on agripreneurship. The participatory format thus transformed a personal disappointment into a communal vision of regeneration.

The Cinematic Language of the Migration Tale Animation

The storyline of Migration Tales from Assam transformed the five original life histories into an ensemble narrative, an aesthetic of plurality. The animation opened at Dibrugarh Railway Station at dawn, where seven individuals viz. Bijoy, Biswajit, Durlov, Rubi, Shyam, Biplob, and Birson embarked on separate journeys but within a shared visual universe. The use of the train as a recurring motif symbolized both mobility and marginality, serving as a moving metaphor of hope and displacement. The melancholic yet hopeful background score underscored what anthropologist Ghassan Hage terms the “politics of waiting,” capturing the in-between temporality of migrants suspended between departure and arrival. Through this cinematic device, the project achieved a form of collective ethnography, where personal testimonies coalesced into a communal archive of motion. Each compartment of the Vivek Express became a microcosm of aspiration, narrated in multiple languages and visual idioms that reflected Assam’s heterogeneity. The use of split screens, flashbacks, and voice-overs mirrored Stuart Hall’s notion of identity as a “production” rather than a fixed essence, illustrating how migrants continually reconstruct themselves across geographies and media forms.

The multi-character script also signified a deliberate shift from individual storytelling to ensemble narration, thereby enacting what Arjun Appadurai describes as a shared mediascape, a collaborative imagination of social futures. By juxtaposing rural flashbacks with urban industrial sceneries, the animation foregrounded migration as both loss and learning. The interweaving of Biplob’s and Birson’s stories one displaced by floods, the other by agricultural stagnation extended the discourse beyond labour migration to include ecological precarity, binding environmental crisis with economic survival. The concluding sequence, where the sun sets over Dibrugarh station, reinstated the theme of circular temporality journeys that end where they begin, yet leave traces of transformation. In this sense, Migration Tales from Assam functioned as participatory cinema of resilience, visualizing migration not as rupture but as relational continuity. The animation’s poetic realism turned ethnographic data into cultural memory, offering an epistemology of feeling that complemented the research’s policy and theoretical analysis.

Synthesis: From Individual Stories to Collective Pedagogy

Together, these animated tales demonstrate the capacity of participatory media to translate micro-narratives into collective pedagogy. Three interrelated patterns emerge:

Economic Reflexivity: Migrants internalized new habits of savings and skill consciousness; animation made these visible for local replication.

Cultural Re-signification: Folk idioms, songs, and dialects embedded in animation re-encoded migration as cultural performance rather than rupture.

Dialogical Agency: Screenings generated inter-generational conversations between parents left behind and youth contemplating migration redefining communication as co-creation. These findings affirm that participatory animation functions as both representation and intervention, simultaneously archiving trauma and cultivating transformation.

Theoretical Discussion: Animation, Mediascapes, and Social Change

1. Dialogical Communication and Conscientization

Paulo Freire’s theory of dialogical communication posits that liberation arises when subjects engage in dialogue to transform their reality (Freire 71). In The Migration Tale, animation operated as a visual dialogue: participants “spoke” through drawing and movement rather than through formal literacy. The act of illustrating one’s life became an act of theorizing it. This multimodal literacy is crucial in contexts of low formal education, where visual expression can equal verbal articulation.

2. Encoding, Decoding, and the Politics of Reception

Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model (Hall 136) elucidates how meaning circulates within participatory animation. The encoding stage involved community members scripting their stories; decoding occurred in screenings where audiences negotiated those meanings. Contrary to top-down communication campaigns, the Migration Tale screenings revealed polysemic receptions, some viewers interpreted Rubi’s independence as feminist courage, others as familial duty. This multiplicity exemplifies participatory democracy in meaning-making.

3. Mediascapes and Vernacular Aesthetics

Arjun Appadurai’s concept of mediascapes (Appadurai 35) helps situate these animations within the global flow of images. While digital tools are global, their aesthetic grammar remained distinctly Assamese: motifs of xorai (ceremonial trays), tea-garden landscapes, and Bihu rhythms. Such localization resists cultural homogenization and asserts regional agency in global visual cultures. The use of open-source software further democratized production, aligning with Rogers’s diffusion theory by reducing barriers to technological adoption.

4. Kinopolitics and Migrant Agency

Thomas Nail’s kinopolitics redefines politics through motion rather than territory (Nail 15). The migrants’ animations literalize this idea, characters constantly in transit, trains and roads recurring as leitmotifs. By animating motion itself, the project enacted kinopolitics as aesthetics: movement became both theme and method, rendering visible the fluidity of identity and belonging.

5. Experiential Learning and Emotional Pedagogy

John Dewey’s principle that learning occurs through experience (Dewey 27) resonates throughout. Workshops functioned as community classrooms where migrants reflected upon their experiences and re-imagined them through drawing. The resulting emotional pedagogy, empathy, recognition, pride surpassed cognitive learning, creating what participants called learning through feeling.

Policy Critique and Recommendations

Despite policy initiatives such as MGNREGA and PMAYG, gaps remain between design and lived realities. Out of approximately 173,000 return migrants, only 33,717 received job cards (PTI 2020). Participatory communication can address these deficits by fostering accountability through localized information loops.

Recommendations

Institutionalize Participatory Media Cells: Panchayats and district labour offices could partner with community radios to document migrant experiences and integrate them into policy review.

Adopt Animation as Pedagogical Tool: Government training centres may employ participatory animation for disseminating knowledge on labour rights, health, and financial literacy.

Bridge Digital Divides: Provide open-source animation training in rural youth clubs, enhancing employability and creative agency.

Data Synergy: Integrate community-generated stories into migration databases to humanize statistics and identify skill clusters for reintegration.

Gender-Responsive Planning: Recognize women migrants like Rubi as independent economic actors; design schemes supporting returnee entrepreneurship.

By reframing migrants as knowledge producers, these measures align with Freire’s ethos of dialogical governance, where communication precedes policy rather than follows it.

Animating Agency: From Oral Testimonies to Visual Collective Memory

The culmination of The Migration Tale was not merely a series of animated shorts but a community archive of emotion. Through animation, ephemeral oral testimonies gained durability; through screenings, private pain became collective reflection. The project thus transformed memory into method, a grassroots epistemology where images replaced reports and empathy replaced enumeration.

Culturally, the animations functioned as a vernacular public sphere. Screenings were often accompanied by folk performances and informal discussions, blurring boundaries between art, media, and civic participation. This convergence embodies what Appadurai calls the “capacity to aspire”, the cultural capacity to navigate and plan futures (Appadurai 59). Migrants, once peripheral in public discourse, emerged as narrators of development, redefining what social change looks like.

The animation practice also revealed the aesthetics of resilience. Each stroke and colour choice was an assertion of existence. As one participant articulated during a feedback session, “When my story moves on the screen, I feel I am still moving, not stopped by the lockdown.” Such affective ownership encapsulates the project’s philosophical core: movement as life, narration as survival.

In retrospect, The Migration Tale Animation Project demonstrates that sustainable communication for development must move beyond transmission toward co-creation. Animation that is collaborative, iterative, and emotional offers a medium where research, art, and advocacy converge. In Eastern Assam, where migration is both livelihood and loss, these animated tales stand as living pedagogies fluid, reflexive, and collectively owned.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 migration crisis in Assam unveiled not only administrative failures but also the potential of participatory media to re-imagine citizenship. By combining ethnographic storytelling with animation, The Migration Tale reframed migrants from data points to co-authors of public knowledge. Grounded in Freirean dialogue and enriched by Hall’s and Appadurai’s cultural theories, the project forged a communicative model that is simultaneously aesthetic, political, and developmental.

The five narratives like Bijoy’s redemption, Biswajit’s craftsmanship, Rubi’s courage, Shyam’s defiance, and Durlov’s hope embody a cinematic pedagogy of resilience. Through community screenings and online diffusion, their stories circulated across villages, catalyzing reflection and local initiative. Animation, in this context, became both the message and the medium of empowerment a technology of empathy translating the invisible labour of migrants into visible art.

Future research can expand this participatory model across other vulnerable regions, exploring how visual storytelling might contribute to policy dialogue and cross-cultural solidarity. Ultimately, The Migration Tale Animation Project demonstrates that social transformation begins when communities not only speak but also see themselves anew moving, animated, and alive.

Works Cited:

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Arya, Sarita. “Domestic Migrant Workers in Kerala and Their Socio-Economic Condition.” Shanlax International Journal of Economics, vol. 6, no. 1, 2018, pp. 74–77.

Deori, Banti. “A Case of Single Female Labour Migrants Working in the Low-End Service Jobs from North-Eastern Region to the Metropolitan City Chennai, India.” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, vol. 21, no. 12, 2016, pp. 20–25.

Dewey, John. Experience and Education. Macmillan, 1938.

Douminthang Baite, N. S., and G. G. Xavier. “Student Migrants in India: A Study on the North East Students in Chennai, Tamil Nadu.” International Journal of Scientific Research, vol. 9, no. 4, 2020, pp. 35–39.

Elkins, John, and Stephen Morton. The Media and Migration: Narratives of Global Mobility. Routledge, 2019.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos, Continuum, 1970.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding/Decoding.” Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, edited by Stuart Hall et al., Routledge, 1980, pp. 128–38.

Kiruthiga, V., and R. Magesh. “The Migration of North East People towards Chennai: A Case Study.” International Journal of Management Research and Business Strategy, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017, pp. 95–97.

Marchang, Ritul. “Out-Migration from North Eastern Region to Cities: Unemployment, Employability and Job Aspiration.” Journal of Economic Social Development, vol. 13, no. 2, 2018, pp. 43–53.

Nail, Thomas. The Figure of the Migrant. Stanford University Press, 2015.

Narayana, D., and C. S. Venkiteswaran. Domestic Migrant Labour in Kerala. Gulathi Institute of Finance and Taxation, 2013.

PTI 2020 https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/over-173-000-workers-returned-to-assam-during-lockdown-state-govt-120083101399_1.html. Accessed on 7 September 2025

Singh, D. P. “Internal Migration in India: 1961–1991.” Demography India, vol. 27, no. 1, 1998, pp. 245–61.

The Sentinel. “More Than 138 Shramik Special Trains Reach Northeast.” The Sentinel, 8 July 2020, https://www.sentinelassam.com/guwahati-city/more-than-138-shramik-special-trains-reach-northeast-487373. Accessed 30 Aug. 2025.

Acknowledgments:

This study and the Migration Tale Animation Project were conducted in collaboration with Brahmaputra Foundation for Social Research and Livelihood Practices, Dibrugarh, Assam and commissioned by IATSS Forum, Japan. The author gratefully acknowledges the participation of the community workers, migrant workers and cartoonist Nituparna Rajbongshi whose stories made this research possible.`